The actual causes of the dissensions between the Prince and his Ministers are not very intelligible at this distance of time. It is certain, however, that Prince Alexander came, rightly or wrongly, to the conclusion that his Ministers were determined to thwart his own policy in every way, and that, in the event of his dissolving the Sobranje, any elections held under the control of the then Ministry would, as a matter of course, return a majority of their nominees. He therefore dismissed his Ministers, and issued a proclamation convoking the Grand Sobranje. In the same proclamation he informed his people that he felt it his duty to abdicate, unless the Assembly should agree to suspend the Constitution for seven years, and to allow him during this period to govern the country without a Parliament. His action may have been unwise, but it was not in excess of the powers conferred on him by the Constitution.

The elections, which were held under an executive composed of his supporters, returned a majority hostile to the late Ministry. Thereupon the Grand Sobranje agreed to accept the terms on which alone the Prince professed himself ready to retain the throne. Owing, however, to strong pressure which was brought to bear upon him from Russia, the Prince gave way within a few months of the extraordinary powers which he had demanded being conferred upon him, and consented to the re-establishment of the original Constitution. Since then there has been no recurrence of this constitutional difficulty.

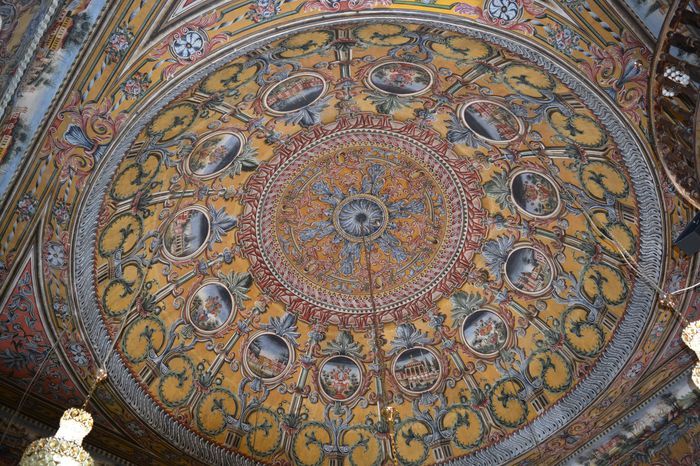

Prince Ferdinand

That this has been so is due partly to the fact that the reigning Prince has shown more good sense and judgment than his predecessor ; partly to the political ability of the statesmen who have held office under Prince Ferdinand ; but, above all, to the accident that, of late years, both the Prince and the Sobranje have had a common interest in avoiding any collision which might furnish an excuse for Russian intervention. The difficulty, however, still exists, though for the present it remains latent.